Is stretching actually detrimental? And if so, how detrimental is it?

When Renato Barosso and his colleagues from from the Laboratory of Neuromuscular Adaptations to Strength Training at the School of Physical Education and Sport of the University of Sao Paulo recruited the 12 young strength-trained men (20.4 years, 67.9, 173.3cm), they probably had a very similar question on their minds.

|

| Figure 1: Graphical outline of the time-course of the 2 x 4 (1RM or maximal repetition) testing sessions (Barosso. 2012) |

- static stretches (SS) This is probably what you would call "the classic stretch", where you hold each stretch for 30s, make a 30s pause and continue

- proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching (PNF) You perform a passive stretch and hold the stretching position for approximately 5 seconds; then, you perform a 5s near-maximal isometric contraction (Sheard . 2010), relax and passively hold the stretching position for another 20s

- ballistic-stretching (BS) Same procedures as in the static stretch session, but instead of holding the stretching positions for 30 seconds, the subjects had to bob in 1:1-second cycles for 1 minute

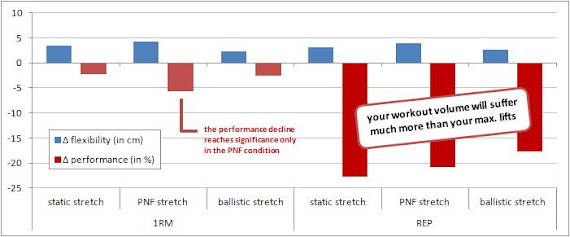

- -8.2 reps (-23%) after the "classic" static stretching routine

- -7.5 reps (-21%) subsequent to the PMF stretching routine, and

- -6.4 reps (-18%) in the maximal rep test after the ballistic stretch

But doesn't stretching help against soreness? No! Neither pre- nor post-workout stretching offer a significant protection against muscle soreness, a Cochraine Review by Herbert et al. from July 2011 found "improvements" of 0.5 or 1pt, respectively, on a 1-100pts soreness scale after reviewing 12 relevant randomized controlled studies, of which one had more than 2,000 subjects (Herbert. 2011).

Despite the fact that the most-heard science based argument against stretching before a workout does in fact involve its well-established negative effects on maximal strength performance, Nelson et al., Franco et al. and Marques et al. reported similar results for knee flexor exercises performed with 40, 50 and 60% of the body weight (Nelson. 2005), 1-3 sets of 20 reps of bench presses (Franco; 2009) and rep-max tests at 40, 60 and 80% knee extensions and bench presses on non-trained individuals (Marques. 2011) as Barroso et al. in the study at hand. The real "news" is thus...So, aside from preventing shortening of the muscles and increasing flexibility is there another reason to stretch? Yes! One surprising finding is that if you are a total couch-potato and don't train at all, 40min of stretching performed 3x / week over the course of 10-weeks will not just increase your flexibility (18.1%), they will also bump your standing long jump (2.3%), vertical jump (6.7%), 20-m sprint (1.3%), knee flexion 1RM (15.3%), knee extension 1RM (32.4%), knee flexion endurance (30.4%) and knee extension endurance (28.5%) performance... what? You are no couch-potato? Great, but these results do still tell you that part of the detrimental effects of stretching on your training performance may well be mitigated by the "training effect" - it's a stressin mini "workout" for your muscles and you would not do 100 body weight squats before your 80% 1RM max-rep test, either - would you?

"[...] that not only SS and PNF but also BS impaired the number of repetitions and the total volume (i.e., number of repetitions x external load) performed after stretching when compared with NS [and] that in strength-trained individuals, only the PNF stretching mode impaired the maximal strength production." (Barroso. 2012)In a more general context, the latter finding, i.e. the influence of the exercise status on the strength declines subsequent to static stretches before a workout, is probably of even greater significance than the notion that you will hamper your strength endurance (note: I stick to this term here, although I am aware that most of you won't think of training at a 80% RM as "strength endurance" training): the questionable significance of data that was generated in an experiment with strength training rookies for the average physical culturist.

In the case of the effects of classic static stretching and ballistic stretches before a workout on the performance during a subsequent 1-RM max strength test, it is now clear that the results from rookies, whose performance drops compared to the no stretch condition, regardless of the protocol, the rookie data is of little to no value for anyone with a coupe of months, let alone years of weight lifting experience.

Bottom line: Irrespective of the last-mentioned problems, the take home message from this and previous studies would be the same for all strength athletes who don't just walk into the gym, crank out a single max set and head home again - Refrain from performing any kind of quasi-static stretching protocol before your workout - and don't forget to look at the study population the next time you see one of the rare studies on resistance training ;-)

References:

- Franco BL, Signorelli GR, Trajano GS, de Oliveira CG. Acute effects of different stretching exercises on muscular endurance. J Strength Cond Res. 2008 Nov;22(6):1832-7.

- Herbert RD, de Noronha M, Kamper SJ. Stretching to prevent or reduce muscle soreness after exercise. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;(7):CD004577.

- Marques MC, Costa PB, da Silva Novaes J. Acute effects of two different stretching methods on local muscular endurance performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Mar;25(3):745-52.

- Nelson AG, Kokkonen J, Arnall DA. Acute muscle stretching inhibits muscle strength endurance performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 May;19(2):338-43.

- Sheard PW, Paine TJ. Optimal contraction intensity during proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation for maximal increase of range of motion. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Feb;24(2):416-21.