|

| Image 1: The "modern" image of the Coke-drinking Santa. Do you really believe he is one of the good guys? |

Is Santa not the good guy, the Coca Cola ads made us believe?

So, if its not the radiation, what else could it be? Could it be Santa Claus himself? Is he haunting us, just as his robotic counterfeit in the distant future of the year 2999, where an evil Santa robot is after the blood of the protagonists of Matt Groening's and David X. Cohens TV series Futurama? Or is it a result of the consumption of too many of the Coca Cola bottles Santa is supposed to have in his bag?

|

| Image 2: One really has to marvel at how the soft drink producers dissolve the enormous amount of sugar on the right in the small amount of dark brew on the left. |

Respiratory diseases. Respiratory diseases increase during winter, and patients weakened by respiratory diseases can die from cardiac diseases. The respiratory hypothesis is undermined by 2 considerations: (1) People dying from cardiac diseases with respiratory disease listed as a secondary cause of death produce a smaller holiday peak than do people dying from cardiac diseases alone: 3.51% versus 3.77%. (2) Interaction between cardiac and respiratory diseases cannot easily explain the twin mortality spikes on Christmas and New Year’s.So, in view of the latest headlines related to "holiday weight gain" here at the SuppVersity and elsewhere on the web, the next best plausible explanation (which would in fact come back to the "Coca Cola < > Santa Connection" ;-) would be gluttony, right?

Holiday weight gain: Distinguishing fact from fiction

Before we jump to any premature conclusions, here, let's initially have a closer look at how much body weight Santa actually has in his bag for you.I mean, the perceived weight gain is enormous, right? Well, science is however not about perceptions and feelings and it should thusly not really surprise you that, according to a US study which was published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine (Yanowski. 2000), the "average" American (in this study represented by 195 US adults with a mean age of 39 +/-12 years) gains no more than 0.37kg, or, expressed in terms of the mean weight of the study participants, 0.5% during the holiday period from from mid-November to early or mid-January.

|

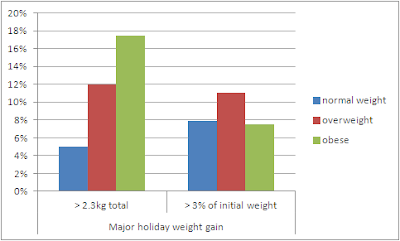

| Figure 1: Percentage of normal weight, overweight and obese subjects with "major weight gain", as defined in absolute or relative terms (data adapted from Yanowski. 2000) |

The real problem is: The weight does not magically disappear

The real culprit is however that the weight people gain during last weeks of the year "is not reversed during

the spring and summer months", so that he researchers' concern that

[t]he 0.48-kg weight gain of the subjects in this study between September or October and February or March might not appear to be clinically important and could easily go unnoticed by both the subjects and health care providers [and that] the cumulative effects of yearly weight gain during the fall and winter are likely to contribute to the substantial increase in body weight that frequently occurs during adulthood.A 2006 by Hull may not only provide a hypothetical explanation for the non-reversibility of the (minor) weight gain (Hull. 2006), it also provides some insights into the true fallacy of "holiday weight gain": The minor increase in total body weight goes at the expense of concomittant increases in body fat and reductions in lean tissue mass.

|

| Figure 2: Relative changes in anthroprometric measures over the holiday season; left axis - overweight / normal weight, right axis + figures - all (data adapted from Hull. 2006) |

Beyond candy, coke & co: Five additional reasons why Christmas is potentially deadly

In spite of the fact that these highly unfavorable changes in body composition are certainly not beneficial for anyone's overall health, it stands out of question that their effects would be cumulative and can thusly hardly explain the empirically validated increased mortality risk during the holiday season. In a 2004 comment on the aforementioned paper by Phillips et. al., Robert A. Kloner thusly proposes five additional hypotheses which could explain the potentially fatal side effects of the holiday season (Kloner. 2004):

- Inappropriate delay in seeking medical attention - best way out: don't wait until all the presents have been wrapped out, when aunt Mary chokes over her food

- Reduced levels of healthcare staffing or fewer staff members who are familiar with individual patients during holiday on-call schedules - best way out: better avoid getting sick in the first place if you do not want to be treated by the SCRUBS staff

- Increased emotional stress - just ignore your nephew when he starts crying because he did not get the Nintendo Wii he wrote on his wish list

- Decreased our of daylight - make sure to get as much of the little light there is during prolonged walks with the whole family (may also help cool down any raised tempers ;-)

- "Postponement of death" - tell your 127 year old uncle that he has been waiting so long now that it would be very inappropriate to die now and ruin everyones' Christmas celebrations